Revolutionary War Uniforms

The Continental Army

On June 17, 1775, a New England colonial army was defending Bunker Hill and adjoining Breed's Hill against an attacking British force seeking to break the Americans siege of Boston. The New England ranks were augmented by small companies of men from Maryland, Pennsylvania and Virginia. The Virginian contingent was clearly distinguishable dressed in ash colored hunting shirts, leggings and round hats in marked contrast to the uniforms of their comrades.The newly appointed Commander in Chief, General George Washington arrived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2 weeks after the Bunker Hill battle wearing the traditional officer's garb of the Virginia militia markedly similar to the cut worn by his British counterparts.

Earliest Revolutionary War Uniforms

|

|

Most of the New England militia men wore a variety of styles evident on Breed's Hill. However, their dress differed greatly from the volunteers of the other colonies. At a later date, General Washington expressed his preference for the Virginian hunting shirt desirable for his Continental Army emphasizing its simplicity and the inexpensive cost.That was not be the case. However, by 1776, the hunting shirt became the standard field dress for such duties as foraging.

However, the more fashion conscious were to win the day when the Continental Congress tackled that problem. Another colonial favorite garment was the weskit or waist coat. The solutions to establish a single standard were to dog them throughout the war.

Some older veterans in provincial regiments repeated or reused the old uniforms worn in the French and Indian wars (1756-63). In those years, both sides of the battle field maintained their sense of fashion. Maryland, New Jersey and South Carolina militias had worn coats of blue with red facing. At that earlier time, a young George Washington (1755) was cognizant of the need for uniformity because it instilled discipline and respect for one's regiment. He ordered, as the new Commander in Chief, that each soldier provide themselves with a coat of blue and red. This color combination would have offered a sharp contrast to the red coated British soldier. South Carolina’s three regiments, in 1775, added a new touch displaying a cap with a feather and the motto, Liberty or Death.

Revolutionary War Uniforms

|

American 1775  |

British 1775 |

French 1760

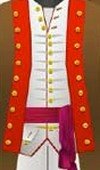

Independent companies were raised by individuals outside of provincial authority. The uniforms were usually paid for by the organizer. Henry Knox, not yet a major general, and merely a Boston bookseller, outfitted his Ancient & Honorable Artillery Company of Boston in a blue coat with red facing similar to the uniform pictured below. Blue became a staple for the artillery. Uniform styles remained stable without any remarkable deviation in cut, but deviations of color were left to the imagination of the buyer. .

American Officer

Revolutionary War Uniform

Major General Nathaniel Greene outfitted his Kentish Guards in Scarlet with green facing. The New York City Bold Foresters, led by Colonel Alexander Hamilton, were attired in green short coats with small hats and brass plate reading “Freedom”. A short coat was quite contrary to the usual military fashion of long coats; most with tails prevalent in revolutionary war uniforms. Artillery men wore dark blue garments with red collars and cuffs and lined their coats in red (1776).

Artillery

Revolutionary War Uniforms

The colors worn on uniforms had more meaning than mere fashion that caught civilian acceptance. It tended to build pride in the company or regiment. Battle fields were often shrouded in cannon and gun smoke. Commanders could discern the uniform colors through the haze and then could order logistical changes of location by identifying friend from foe. The British red coat, or the blue color used by the Continentals, would distinguish friend from enemy in the chaos of a battlefield.

Classic British

Revolutionary War Uniforms

King's 8th

Military fashion tended to follow styles embedded in civilian society. The three cornered hat had been a staple fashion for 100 years.The style was followed by the Continental troops. In an attempt at military elitism, their field officers attached red or pink cockades to the hats. Captains displayed their cockades in yellow or black. This adornment signified the French alliance. When this tri-cornered hat was discontinued by civilians, the hat lost favor with the military.

Revolutionary War Uniforms

|

|

The American light Dragoons wore blue with a white lining and white buttons. Some regiments had buttons inscribed with regimental designations. Some used pewter. They favored a heavy leather hat with brass trimmings with the added touch, a horsehair crest. More significantly, the saber they carried was a deadly weapon when propelled by a charging warhorse.

Accouterments of

Revolutionary War Uniforms

|

|

The gear carried by soldiers was common to both armies. Their kit included a musket with bayonet, rifle without bayonet, cartridge box, powder horn, canteen of wood or tin, haversack to carry rations and knapsack to carry personal items.

Officers owned two swords. One used for full dress--ceremonial in character, and the other in battle used primarily in hand to hand battle. General Washington considered his sword a definitive part of his uniform. The relationship between sword and officer was succinctly described by Donald N. Moran in an article for the Sons of Liberty. He wrote, "to a military officer it was an emblem of his rank and often a reward for gallantry----". And "To the common soldier or sailor it was the weapon of 'last resort' ".

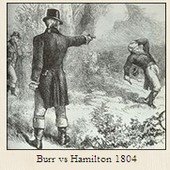

The pistol was very inaccurate and worn by officers and cavalry men. The pistol, like the sword, was as much a part of the uniform as the jacket. A wit wrote, tongue in cheek, it guaranteed the survival of the duelists---but don't tell that to Alexander Hamilton.

|

|

Actions of Continental Congress

Establishing

Standards for Revolutionary War Uniforms

1775: The Continental Congress appointed one of its delegates, George Washington, Commander in Chief of the Continental Army. He began to form a headquarters staff. Although those who were chosen, as well as the delegates to the congress. were well read, few had held significant military positions that equipped them to operate a major war.

The question of supply was a persistent undercurrent in most deliberations. Clothing the army was one major priority.

There was no officer class maintained in the militia system. No military minds ready to take over the issues of supply in the Continental Army.

None had ever dealt with supply agents required to form a chain.

In an early congressional resolution, they tasked General Washington to appoint a "Clothier General".

General James Mease was chosen. He immediately had to create sources of supply but was constrained to operate without any formal structure. Abuses surfaced at once. General Washington, in years to come, would not only reflect on the lack of a system, but also the lack of civilian cooperation that had become war weary.

In his first Council of War in 1775, Washington advised his commanders to clothe their soldiers, each officer, according to "his own fancy". The result was a variety of colors. One officer chose a red coat that could pass the test of a British sergeant. When viewed by Washington, he ordered that the coats be dyed brown. General Mease advised that the dye would not work well. Washington quickly learned the art of compromise. The coats could be worn only beneath an outer garment. The standard outer garment attempted to be weather friendly and hid the red undergarments that could be disastrous in close quarter battle with the British "red coats".

The consensus that brown would be the standard color of uniforms was more honored in the breach. Officers gravitated to blue, and by 1778 the lower ranks trended toward the blue color. Nevertheless, supply was a factor and brown dyed material was more available.

Revolutionary War Uniforms

Copyright and photo courtesy of Sherie Selander, The Quartermaster General

As the army grew, the demand for clothing exceeded the supply. Clothing became a medium of exchange. At one point, later in the war, this exchange involved uniforms for whiskey. Naked and drunk on duty!

A plan was hatched to pay for uniforms. It followed the British system that required their soldiers to pay for all clothing issued by the army by automatic payroll deductions. The Continental soldier was subjected to a monthly wage deduction of $1.75.

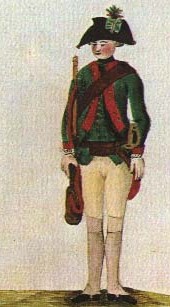

Scarcity of cloth was on the near horizon.There was a desire to create a standard color. 1775 did not to fulfill that wish. Over the course of the war, brown, blue and green became the predominate uniform colors. Green was adopted by many of the riflemen of the Continental army and worn by their counterparts in the Hessian forces as an aid to a hidden sniper in a forest. . Supply and availability would determine color at any one time.

Revolutionary War Uniforms

|

|

1776: Congress established a Secret Committee which contracted with New England merchants to import brown and blue cloth from France. Shoes ordered from France would prove to be a bad investment. They were too flimsy for American terrain and the wear and tear sustained over long marches. Nevertheless, without foreign aid and assistance from France, the new nation could never have prosecuted the war.

In this same year, a soldier remarked in the retreat from New York, that he observed a comrade wearing raw animal hide on his feet. The day before it had graced the body of a cow slaughtered for food. The order issued by General Mease in 1779 to establish a Hide Department had been no help for this soldier.

Many shoes did not come in left, right pairs. Same size would fit either foot. When high top boots were available, they were designated for the cavalry. Most soldiers wore moccasins or whatever was at hand. Shortages revive images of soldiers at Valley Forge wearing strips of blankets on their feet or just bare in the snow 1777-1778. A writer pointed out that death from hunger was more fatal than the sword. Cold could easily be substituted for hunger.

Shortages of Revolutionary War Uniforms

|

|

The riflemen sharpshooter and the rangers were clad in green. Finally, someone understood the value of camouflage. Their comrades and the enemy labored under cumbersome and colorful uniforms that made excellent targets. As the American forces grew, so did the variety of styles and shapes of hats, gaiters, and half-gaiters.

Revolutionary War Uniforms

Shipments from Europe would remain a problem throughout the war due to interdiction on the high seas by the British navy. Those ships that safely crossed the Atlantic had the additional problem of finding a safe haven on shore when New York and Philadelphia were occupied by the British. Ships that landed in New England with material, or other supplies destined for troops further south, created a new problem. The cost of cartage skyrocketed. There were opportunities for profiteers and there were no shortages of that ilk. Needless to point out, the young American navy was equally active against British supply ships.

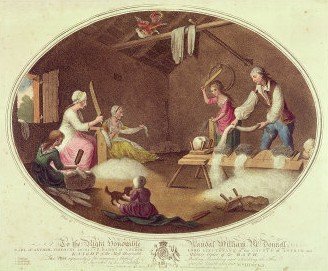

1777-78: Congress ordered 40,000 uniforms for its expanding army either brown or blue with red facing. Delivery from France was made 1 ½ years later. Production of linen for shirts was dependent on a domestic supply from farm households growing flax.

Producing Revolutionary War Uniforms

1778:This was the year of the clothing crisis. The demand for cloth had reached a crescendo. There were shortages suffered by the civilian population accentuated by the needs of the military. Shipments were hijacked. Military goods passing over the roads destined for shipment to army units in other states were commandeered by state authorities to be distributed to their own militia. Both the roads and cartage were rudimentary and added to the transport problem of military materiel. Finally, General Washington retaliated. He ordered his commanders to seize shipments no matter their ownership or destination.

The Continental Congress appointed a clothing committee and set so many rigid rules that the system was paralyzed with regulations. The states had no understanding of the value of pooling resources.

There was a complete lack of experience with secondary suppliers. Middle men, if you will. Ultimately, the congress created a Board of War and a War Department.

They endowed the 3 person board with executive authority, and in a sense, established an early cabinet type agency.

The shortages became an enlistment tool.

A bounty of $20.00 was paid to a recruit if he supplied his own kit provided the following were certified to be in the possession of the soldier: 2 linen hunting shirts, 2 pairs of overalls, leather or woolen waist coat with sleeves, 1 pair of breeches, a hat or leather cap, 2 shirts,2 pair of hose, 2 pair of shoes. The heavy regimental coat reflecting its common color was required to be worn in battle no matter the heat. An option to the coat in some units was the dyed, homespun linen coat.

Revolutionary War Uniforms

Courtesy C&D Jarnigan Company |

|

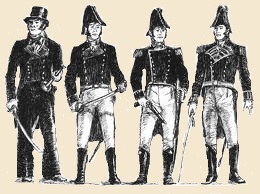

1779: By authority of Congress, Washington ordered blue coats, white vests, facing and buttons optional. Different colors for linings and facings differentiated state regiments incorporated into the Continental line .

Officers wore blue coats, white vests, waist coats and breeches of buff or white. Rank was displayed on shoulder epaulets following the British style.

|

Field Grade Officer Non Commissioned Officer |

Many uniforms were obtained from captured British stores. Spain’s sea engagements with Britain resulted in 3,000 captured uniforms shipped to the Continental Army. An American fleet entered Narragansett Harbor and captured the British vessel Mellish. Thousands of British uniforms destined for Canada found there way onto the backs of the Continental Army. American history was introduced to the significance of the common sailor and specifically a young naval lieutenant's part in the American naval offensive. In a short period, John Paul Jones would be elevated to command a fleet.

Revolutionary War Uniforms

|

|

British Army

and Navy

Revolutionary War Uniforms

The British Revolutionary War uniforms were no less colorful than the Americans. However, the term "uniform" also was synonymous with the term "standardization". The "Red Coat" will always be remembered as standard British issue. And more derisively referred to by the Americans as "lobster backs".

Their hats were unique. The grenadiers (infantry) wore bear skin caps with a tassel and cap plate. The Cold Stream Guards wore a cocked hat with a button ornament. Dragoons (cavalry) sported a hat with horse hair plumage and chin strap. Often worn in ceremonial dress and referred to as a shako.The tall cylindrical hat would be very popular in the French Army particularly during the Napoleonic era.

It was standard procedure for the army to distribute the uniform to recruits and then deduct its cost from monthly wages.

The pride and authority of rank was displayed on the officer's shoulder.

Some European regiments identified themselves with a metal breast plate, an inscribed gorget, worn like a necklace. There were some American officers that copied this affectation.

Copyright and photo courtesy of Sherie Selander, The Quartermaster General

Buttons were often inscribed identifying the regiment. Butler's Loyalist companies sported pewter buttons with the regimental name. Other stylish accessories were belt plates and badges.

Copyright and photo courtesy of Sherie Selander, The Quartermaster General

The British sword, the Hanger, was standard issue and first manufactured in 1751. It had a slightly curved blade, 27 inches long, with a brass hilt and guard. The same weapon was used by the German auxiliaries. Generally, the quality of construction and steel was superior than that forged in America.

Supplies became more problematic as the war proceeded, but they, unlike the Americans, had an experienced quartermaster staff that had centuries of time tested guidelines. A popular treatise of the era was "The Military Guide for Young Officers", by Thomas Simes. This was almost required reading for budding officers and included a section on the duties of supply officers.

The backbone of British power was its navy. They sang the praises of the naval service which included the refrain, "Britannia rules the waves". There was a subtle difference in uniform styles as the "sailing man" rose in rank.

Distinguishing Naval Rank

Revolutionary War Uniforms

German Auxiliary

Revolutionary War Uniforms

The German States furnished the British Army with 30,000 experienced, battle hardened veterans fresh from the European wars. Their uniforms were masterpieces of color and substance. Hardly an unusual display when one views their regimental flags. Each German regiment had its own style and reflected the character of the force and the choice of their commanders. Hessians formed a sizable portion of the German contingents leased en masse to the British government.

Although stylistically colorful, the uniforms belied the fancy appearance.The fabric was coarse and approximates current burlap. The cloth was densely woven with an eye toward durability. All soldiers wore blue coats and the facings (lapels, collars,cuffs) were left to the regiment to decide. The Jager units of riflemen wore green with red facing. The soldiers were to be reissued new uniforms once a year. Supply never caught up to this agreement.

|

|

The Hessian boot was standard issue. You might see in it a forerunner of current styles. It had a semi pointed toe that could easily slip into or out of a stirrup. It had a tassel at the top which fell just below the knee.

The officer carried a slender sword that required intensive training to master the thrust and cut tactics. The ordinary infantry man used the British Hanger more like a saber used in close quarter fighting.

The tall hat with its brass plate could be distinguished from that of any other army.They were almost exclusively worn by grenadiers. Most other elements of the German forces wore the similar tricorn hat worn by American troops. The grenadier had been chosen for his height and strength. Adding inches to his above average height created an illusion of a charging giant at the back end of a bayonet. In the early stages of the war, this perception created panic in the American ranks.

Sources:

A History of the British Army, 13 Vols. (London 1899-1930).

Emerson, William K. Encyclopedia of United States

Army Insignia and Uniforms.

Mollo, John. Uniforms of the American Revolution. New York. Sterling.1991.

Moran, Donald N. Sons of Liberty Chapter. June/July 2004 Edition.

The Visual Dictionary of Military UniformsNew York,

New York. Dorling Kindersley,

Inc. 1992.

The Writings of George Washington. ed. John C. Fitzpatrick, 30 Vols. (Washington 1930-39).

Troiani, Don. Soldier's of the American Revolution

www.thequartermastergeneral.com

References:

Library of Congress

New York Historical Society

Uniforms of the American Revolution, Sons of the Revolution in the State of California.