Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Recognition of the Mental Component

The common denominator in any study of past American wars begins with the casualty lists. The wounded are usually represented as greater in number than the dead. The injured were visibly identified by some portion of the body that was pierced, torn or cut. Until recently, it was implausible that anything other than physical damage would exempt men from battle. Historically, it was impossible to convince the military of the existence of non visible wounds that rendered a soldier medically disabled. There is extensive evidence that the symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome were well documented in the annals of war. Although symptoms of PTSD were a consistent, disabling thread, they were routinely dismissed as wounds. Before Post Traumatic Stress Disorder was an accepted psychiatric diagnosis in 1980, (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders) field commanders and military doctors often recognized many of its manifestations. Nevertheless, even the perceptive were short sighted. No blood, no glory, no wound.

The operative word in Post Traumatic Stress Disorder is "stress". It is defined as "a mentally or

emotionally disruptive or upsetting condition occurring in response to

adverse external influences and capable of affecting physical health,

usually characterized, by increased heart rate, a rise in blood pressure,

muscular tension, irritability, and depression." We will note

throughout this review that stress is a potent source that can initiate mental disorder or exacerbate an existing illness. Stress is not confined to the battlefield, and, when uncontrolled, it can affect any individual. It can even appear in childhood and precipitate neurological disorder in the healthiest child as well as finding easier targets like those saddled with tourettes.

An award winning, peer reviewed study conducted by J. Douglas Bremner for the Pandora's Project concluded:

"Traumatic stress, such as that caused by childhood sexual abuse, can have far-reaching effects on the brain and its functions. Recent studies indicate that extreme stress can cause measurable physical changes in the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex, two areas of the brain involved in memory and emotional response. These changes can, in turn, lead not only to classic PTSD symptoms, such as loss and distortion of memory of events surrounding the abuse, but also to ongoing problems with learning and remembering new information. These findings may help explain the controversial phenomenon of "recovered" or delayed memories. They also suggest that how we educate, rehabilitate and treat PTSD sufferers may need to be reconsidered."

There are numerous recorded accounts of PTSD symptoms stemming from an

unseen, internal force in situations other than combat. It was no

great leap of faith to identify many symptoms arising out of a

particular incident as an immediate trigger. In 1660, the famous

diarist, Samuel Pepys, an eye witness to the Great Fire of London,

observed a paralyzing fear in the citizens of the city. It did not

escape his objective eye that he also was having difficulty coping with

the event. His normal sleep patterns were shattered although his

property had escaped damage. A body of evidence would build in the

ensuing centuries that stress symptoms were not the sole province of the

military. Singular incidents of sexual abuse, holocaust survivors, and

serious auto accidents affected some civilians with similar symptoms as

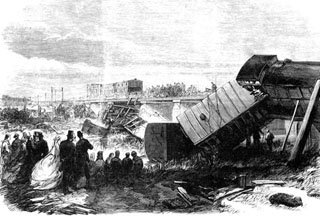

those affecting men in battle. In 1865, Charles Dickens had a

brush with death in the Staplehurst Railway accident. His car was the

only one in the first class section that did not fall into the nearby

ravine. As a witness to tragic deaths and serious injuries, he

suffered long bouts of insomnia--repeating the Pepys experience two

hundred years earlier. Each man encountered a frequent symptom of PTSD. Left unstated was whether nightmares encumbered their fitful sleep.

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Evolution of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Many of history's stress affected warriors had proven their heroism in battle. It defied rational explanation that they were no longer fit for duty although physically unscathed. Herodotus (484-425 b.c.e.), the reputed father of history, had personal knowledge of the last years of the Greco-Persian Wars, and had contact with survivors of those war years prior to his birth. He reported in his written history of the Battle of Marathon (490 b.c.e.) that one Athenian suffered unexplained blindness when a nearby soldier was killed. Ten years later Sparta's King Leonidas excused men from battle when he found that they had no "heart" for the fight. They were physically spent by the weight of prior battles. Herodotus touched at the core of mental abnormality when he reported that a warrior, known as the "trembler", inexplicably hung himself after a battle. In an earlier historical footnote some 2,000 years before the ascendancy of the Greeks, an Egyptian soldier recounted the "trembling" of some warriors while advancing in battle.These symptoms were noted but never correlated with wounds.

In 1678, Swiss military doctors, ascertained that soldiers with symptoms of a racing or irregular heart beat were susceptible to sleep deprivation and often appeared dazed. With brilliant insight, they blamed the individual's state of mind which was a tacit understanding that the problem originated below the surface. However, that diagnosis fell far short of connecting "state of mind" with the brain or central nervous system. They searched for a rational explanation that fell within the common experience of those affected. They concluded, that some men missed home and hearth more than others.They coined the term "nostalgia"---later referred to as homesickness. That term remained in the military lexicon for another century and undoubtedly was transported to America. However, a search of the literature fails to reveal any evidence of PTSD symptoms in the American Army either during the Revolution or the War of 1812. In hindsight, it was simply ignored, or the practice of short term enlistments obviated symptoms of "nostalgia". In the light of later knowledge, eliminating constant, repeated exposure to battle may have relieved stress causing symptoms. In any event, it was a universal conviction that cowardice, a character defect, easily explained evidence of personal disorder. Commanders knew that terror was contagious and thwarted discipline, and cowards contributed to the breakdown of moral. In 1727, many defenders of Gibraltar refused to continue fighting despite whippings and other harsh punishments. Publicly eliminate the coward, set an example for the troops, problem solved. The reality is that it was never solved.

During Napoleon's reign, Dominique-Jean Larrey was Surgeon in Chief of the French Army. Larrey has been acknowledged as the first modern day military surgeon. He was known for his humane treatment of the wounded. In 1815, he was recognized by the English General Wellington at Waterloo for his humanity on the battlefield andthe English were directed not to fire on him. While likely working within the parameters of the "Nostalgia" diagnosis, he propounded its three stages: heightened excitement and imagination, fever and gastrointestinal problems, depression and frustration. Scientific minds were grappling with symptoms, but came no closer to its causes. Why would men react differently to the same fear inducing incident? Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Musée du Louvre, Paris.

The Civil War (1861-1865) and its repeating rifles marked a cross road in the history of war. Americans were now fully engaged in modern warfare. Stressed morphed into terror as troops charged across fields into the mouths of cannon fire. Companions over dinners the night before were falling with gaping wounds the next morning. Soldiers who held back, or turned back without orders to retreat, were believed to be malingerers--or worse, cowards. Those that recognized something deeper than these derogatory descriptions were still relying on "nostalgia" for an explanation. On its face, the northern civilian turned soldier who refused to fight in Tennessee was deemed homesick. When an epidemic of similar situations arose, and soldiers appeared to be in the throes of uncontrollable trembling or shivering, terms like "nostalgia" and "homesick" were an unacceptable explanation. These evaluations were no longer in fashion and about to be referred by some military medics to the hazardous waste of prior centuries. The doctors began to call these cases "irritable heart". They were supported by the data that disclosed those suffering had racing hearts. Those soldiers were no longer suffering from home sickness, no longer cowards, but severely ill and mired in deep melancholy. This was hardly a giant step from the view of the Swiss doctors two hundred years earlier.

The worst cases were discharged from further service. The government in the north, hardly convinced, opened the first military hospital for the "insane" which it would close soon after the war. "Nostalgia" persisted as a diagnosis and dueled with the "irritable heart" theory.

Government investigators surveyed the field and found dazed soldiers wandering the countryside and literally starving or freezing to death. These befuddled souls may have awakened the public and the impetus for establishing a hospital to care for these men who had lost control of the most basic functions of living. Author and historian Bruce Catton was an eye witness to the slaughter. He famously wrote that war, once in motion, was beyond the control of man---and by extrapolation----man losing control of himself. A later historian, and author of 'No More Heroes', Richard Gabriel, sagely observed that only the sane become insane in combat, and the already insane fit neatly in an officer's battle plan. Dr. Robert Lifton, in a contemporary study, supported this thesis finding that the sane are the soldiers that suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. In another echo of this premise, Dr. Victor Frankel, a survivor of a concentration camp, in Man's Search for Meaning", cogently stated, an "Abnormal response to an abnormal situation is in reality normal behavior".

As we trolled the literature and then the internet for further evidence of 19th century military stress, we located one in the most surprising setting. On June 25, 1876, the Sioux Nation and their allies attacked and annihilated a battalion of the U.S. Seventh Cavalry led by George Armstrong Custer at the Little Big Horn River. His second in command, Major Marcus Reno, had been ordered to attack the Sioux camp from another direction and act as a blocking action for escaping Indians that would supposedly flee from the Custer attack. Reno's Indian scout, Bloody Knife,standing next to Reno, was struck by a bullet to the head. The blood and gore sprayed onto Reno who became paralyzed with shock. He began to cry uncontrollably and later claimed to have heard voices in his head. All are classic symptoms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder reacting to a violent incident. He appears to have quickly recovered to lead his companies. He was later charged with cowardice but was exonerated in a trial with reputedly coerced testimony from junior ranks.

The back story: Prior to Little Big Horn, Reno had seen action in the civil war. Early in the war his horse had been shot from under him and had fallen on Reno breaking his leg. Then in 1863, he again saw action on the bloody fields of Gettysburg, and a year later at Cold Harbor. By all measurement he was an exemplary soldier and he had been decorated for gallant and meritorious conduct. He may have never recovered from the repetitive and accumulated stress.

Post Little Big Horn he was court martialed for drunkenness and conduct unbecoming an officer. After a pardon by President Rutherford Hayes, he returned to service. He was again charged (1880) and convicted of drunkenness and given a general discharge. He died penniless and without funds for a train ticket to attend his son's wedding. In 1967, he was posthumously granted an honorable discharge

Reno's behavior is a classic case of a "Hero No More". It would take a century to classify this man's prolonged exposure to the stress of battlefields and his responses to the terror it evoked as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. One writer succinctly nailed it and wrote "Emotional stress builds very rapidly in combat". In 1905, at the height of the Russo-Japanese conflict, Russian military doctors began to recognize symptoms of stress occurring most frequently at the front lines. Proximity would ultimately be a pillar of PTSD causation.

Charles Russell |

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder |

In the Spanish American War in 1898, only a ten week campaign, a young officer, John Pershing, noted an usually high incidence of mental illness. The consensus was that these soldiers were exposed to explosions from large caliber cannons and sustained a concussive effect to the brain. The "shell shock" diagnosis would follow him into World War 1 when he became Commanding General of the American Expeditionary force in France.

During this era, the

noted psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud deemed that soldiers were suffering

from a war neurosis (emotional disorder without apparent change in any

organ). Freud viewed this as a conflict between a "war ego" and a "peace

ego". Although his "neurosis" diagnosis is no longer an acceptable

scientific theory, his other conclusions that incidents in the life of a

child can influence adult behavior is still viable.

The American casualties in World War 1 (1917-1918) included 204,000 wounded in action. Not included were the 159,000 withdrawn from action because of mental breakdown leading to the discharge of 70,000 men. The conscription process began to screen for those "predisposed" to emotional breakdown. There were no fixed standards for the commissioners of the draft, and as many as several million may have been exempted from service. On the other side of the lines, Germans were also suffering mental illness. In the famous novel "All Quiet on the Western Front", the author, Erich Maria Remarque, recognized that many men were discharged in a state of 'bewilderment". In his sequel, "Three Comrades", the story of German veterans, he featured ex-soldiers who disassociated from society.

The data began to build that soldiers who exhibited depression, anxiety, confusion and insomnia while in uniform continued the same patterns when they returned to civilian life. Proximity to the heavy explosions of big cannons were believed as the source of the problem and, hence, the soldiers were deemed "shell shocked". The scientific community was ready to erase the earlier theory based on a racing heart beat.The newer diagnosis now leaned toward brain damage from the bombardments.The theory gleaned from the Spanish American war had gained traction in the "war to end all wars".

www.dailymail.co.uk

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

It appeared to military doctors that the explanation for the variety of symptoms ranging from fear to disorientation could be found in the proximity to bombardments. It followed, according to their rationale, that the injury was located in the brain---it was physical and the waves emanating from the explosions created a concussive effect. As in any concussion, a quick recovery was diagnosed as less severe, and the effects that lasted longer were regarded as a severe concussion. Those soldiers that appeared never to recover were deemed to have suffered irreversible injury to the brain. This latest diagnosis began to mute insults of cowardice.This was hardly gratifying for the 300 British soldiers executed during the war for cowardliness. In 2006, they were posthumously pardoned.

It would take another 60 plus years and three more major American wars to understand that the damage to the soldiers was not confined to the physical, but it was also psychological.

During World War 2, American commanders displayed little compassion for those afflicted with the symptoms of the yet to be established post traumatic stress disorder. This lack of recognition ignored the significance that of the almost one million soldiers who saw direct combat action (American involvement 1941-1945), thirty-seven percent would be discharged for "combat exhaustion". Later it was rebranded as "combat fatigue". The medical community failed to offer any new guidance. It was their general belief that an individual's predisposition was an underlying cause. The therapy for those suffering overt signals was aimed at returning those men to duty--- effectively re-exposure to the scene of the crime. For the most part, a temporary vacation termed R&R (rest and relaxation) was viewed as the primary cure.

During the invasion of Sicily in 1943, a young private serving in the U.S. 26th Infantry Regiment reported to his medical aid station in June. He required treatment for "battle fatigue". He was transferred to the medical evacuation hospital and administered sodium amytal. (This drug is administered intravenously and acts as an hypnotic sedative on the central nervous system.) The soldier's medical notes read in part, "psychoneurosis anxiety state----he is repeatedly returned to the front". Lt. Gen. George Patton, Commander of the 7th Army, entered the tent in which the private was housed. His intention was to tour the hospital and speak to the wounded. He approached the listless private and asked him where he was wounded. The private responded that he was "nervous" rather than wounded. Patton slapped the soldier across the chin with his gloved hand and pulled him out of the tent. The general kicked him in the rear end yelling" ---- you gutless bastard--your going back to the front". Medics returned him to the tent and found he was running 102.2 degree temperature. They added to his chart "malarial parasites". Whether this was an ad hoc diagnosis to prevent his return to the front when demonstrably ill, no one will ever know. Records disclose that a large number of soldiers suffering psychiatric symptoms were evacuated from Sicily, and only 15% were returned to duty.

In mid summer, Patton was still fuming about "yellow bellies". He issued this directive forbidding a battle fatigue diagnosis:

"It has come to my attention that a very small number of soldiers are going to the hospital on the pretext that they are nervously incapable of combat. Such men are cowards and bring discredit on the army and disgrace to their comrades, whom they heartlessly leave to endure the dangers of battle while they, themselves, use the hospital as a means of escape. You will take measures to see that such cases are not sent to the hospital but dealt with in their units. Those who are not willing to fight will be tried by court-martial for cowardice in the face of the enemy. —Patton directive to the Seventh Army, 5 August 1943.

As if to punctuate his order, on August 10, 1943

, Patton again toured a hospital in Sicily. A private from the 1st

Infantry Division had been admitted with symptoms of confusion, fever

and fatigue. Prior to admission, he had tried every means to avoid

separation from his unit. This guilty feeling of abandoning comrades

often turned into a lifetime disability.

Patton took note of the G.I. who was trembling and asked him what his problem was. "It's my nerves. I can't stand the shelling anymore." Patton slapped the private and drew his pistol and pointed it at the young man, as if to execute him on the spot. Medical attendants defused the situation. Whether at this time, or later, members of a medical team heard Patton utter that "the condition" was the invention of the Jews---possibly referring to the Jewish doctors in service.

This second slapping incident spread virally in the U.S. news services. General Eisenhower, already aware of the incidents, had sought to keep it under wraps. He could no longer do so with the press and public calling for Patton's dismissal. It is commonly believed that Patton lost his command because of the incidents. Actually, the the break-up of the 7th Army had been in the works prior to the problems caused by Patton. Eisenhower wrote the following order:

"I clearly understand that firm and drastic measures are at times necessary in order to secure the desired objectives. But this does not excuse brutality, abuse of the sick, nor exhibition of uncontrollable temper in front of subordinates." ... "I feel that the personal services you have rendered the United States and the Allied cause during the past weeks are of incalculable value; but nevertheless if there is a very considerable element of truth in the allegations accompanying this letter, I must so seriously question your good judgement (sic) and your self-discipline as to raise serious doubts in my mind as to your future usefulness". —Eisenhower's letter to Patton, dated 17 August 1943

Patton

was forced to personally apologize to the two soldiers. He was hardly

repentant. When he learned that his friend and teacher, General John

Pershing, a hero of two prior wars, had condemned his actions, he never

spoke to him again. Patton would continue to preach that soldiers had to

learn to cope with battle conditions.

In 1947, a

paper by Kardiner and Spiegel, "War stress and Neurotic Illness", barely

was noted by the military. It described "persistent, chronic and war

induced neurosis". The symptoms most apparent were irritability and

impairment of cognitive functions. A study in the 1950s reported

in the American Journal of Psychiatry was a follow up of 200 World War 2

soldiers who had experienced the classic PTSD symptoms in service. Ten

years after the fact, the symptoms had hardened into chronic illness.

The report made no effort to separate itself from the war years

diagnosis, "traumatic war neurosis". Another unique follow up study of

Dutch resistance fighters in 1993 found that 35 years after World War 2, some were suffering from a delayed onset of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder.

Prior to the Vietnam War era, it was hard to shake the common belief that soldiers, and other victims of trauma, were morally weak, basically cowards, and even masochists. The Korean War was no exception. This view was prevalent despite the fact that of the 200,000 Americans who served in combat, 24% sustained some mental disability without an insightful diagnosis. Many of the veterans would take on no civilian task that had any relation to war.

A marine who was part of an American mass retreat at the Chosin Reservoir (after an attack in North Korea by Chinese regular troops November 27-December 13, 1950) was asked what he wanted for Christmas. He answered. "tomorrow". That was a sign of desperation that fueled anxiety, fear and ultimately could undermine rational cognitive functions.

The ten years of the Vietnam War (1965-1975) was the red line that could not be ignored by the military and the medical profession. The Research Triangle Institute, after hostilities ended, found as many as 480,000 men suffered from some of the following symptoms: anxiety, flashbacks, insomnia, nightmares, diminished cognitive skills. Another 350,000 were found with partial symptoms. Remarkably informative was that 26.5% women in the combat zones also had significant symptoms. 31.9% of the men developed Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. The investigators estimated that 20%, or more of the soldiers in both World War 2 and Korea suffered from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder. They never received proper treatment. The standard treatment in Vietnam for depression, anxiety and hysteria was the tranquilizer, Thorazine. If that did not work, then a bit of R&R in Saigon would do the trick. Medical records meticulously avoided psychiatric terms that might later haunt the patient. Scrubbed records might read, "acute situation reaction". After being returned to duty, there were no medical follow-ups, no checking on future behavior and no collection of information on any intentional injury to one's self or buddies. Alarmingly, no relationship between any former "illness" and the shooting of unarmed civilians was investigated. The complete MY Lai Massacre record (March 16, 1968) makes no mention of any prior medical history of the men involved.

As the war in Vietnam lingered over the long years, the term "combat

neurosis" made its appearance in the psychoanalytical vocabulary. This

signaled an intent to examine personality disorder, unresolved childhood

problems and deeply rooted anxieties. Looking in this new direction, while on closer examination was self defeating,

would ultimately negate theories that claimed PTSD symptoms stemmed from exhaustion or neurotic

tendencies. Unfortunately, these new approaches were largely ignored in

Vietnam.

What would trouble the medical profession was the

fact that the symptoms continued long after soldiers were discharged.

Cross class analysis also found

similar signs of disorder in the non soldier. In the civilian

population, psychologists were tracing, in many cases, symptoms to a

rape, child molestation or spousal

abuse.The flashbacks, nightmares, reliving the event was disturbingly

similar to the experience of the soldiers in combat. The conclusion was

inescapable. These experiences were unrelated to exhaustion or neurotic

tendencies. We now know that time spent in combat, even a single stress

inducing experience, or repeated deployments with close

proximity to combat is a leading cause of PTSD. More than 90% of those

affected soldiers reported that they either were shot at, and at the

very least,

a participant in a fire fight.

General Norman Schwarzkopf who led American and coalition forces in the Desert Storm War in the Middle East (1990-1991) was now aware of the debilitating effects of PTSD. He could empathize with those soldiers suffering the visible evidence of stress. Although the war was of short duration, and casualties were light, 10.1% of the men in combat reported PTSD symptoms as against 4.2% in support roles.

When a reporter at a briefing questioned the General as to why

he had not landed marines on a mined Kuwaiti beach he recalled an

incident when he was a young captain in Vietnam. At the time, he was an

adviser to a South Vietnam Ranger team (1965) that was caught in a

Viet Cong minefield at night. He recalled the terror of bodies blowing

up around him. His team crawled through the field on their bellies in

total

darkness. Each soldier extending a knife or bayonet before them to feel

for trip wires or

detonators. His response to the newsman was: "Have you ever been caught

in the middle of a mine field and had to work your way out of it ?" It

was in such a moment that the line between rational thought and

potential cognitive dissonance can be breached.

Studies and Therapies

General Schwarzkopf's response to the reporter is a starting point to understand PTSD. The trauma of lying inert in a field of flying body parts, without an obvious means of escape, is a potential trip wire to PTSD. The longer the exposure to this type of stimulus the stronger the surge of stress. At its apex, acute stress can create harmful physiological changes. Neuro-biochemical research revealed that traumatic events can cause lasting damage to the nervous system.

The physiological reaction to stress is referred

to as "fight or flight"---survival. The instantaneous decision is whether to stand

and fight the threat or flee. It is the beginning of a process that

regulates the behavioral response to the stress inducing stimulus. It is

in lay terms a coping mechanism that controls the reaction to a

menacing situation. The changes occur in the central nervous system that

controls blood pressure, immediately directs the flow of blood to areas

such as muscles that require added strength to meet the perceived

threat. When the stress grows, so will the intensity of the response.

The immediate reaction to a threat triggers hormonal activity. Three major hormones actively control the emotional response of "fight or flight". Adrenaline is the hormone that controls immediate reactions to a stimulus and accounts for breathing faster and sweating that prevents the body from overheating. Feeling faint after the reaction of the "fight or flight system" has diminished may occur if the adrenaline was produced in excess. Norepinephrine acts as a back up to adrenaline that is secreted both from a gland and from the brain causing blood flow to be redirected to areas most needed in response to the stimulus such as a particular muscle group. It has an arousal effect that permits a more focused response to stress. Cortisol is a slower acting hormone that handles stress over a longer period than the other two hormones. Excessive production of cortisol can suppress the immune system and damage tissue. Too little secretion causes fatigue. It is also referred to as the "life saver" when functioning properly.

Cortisol is closely connected to PTSD. Cortisol can be

continally released before and after an incidence of stress.Here is how

the cortisol works. This occurs when the amygdala

portion of the brain recognizes the threat and signals to the

hypothalamus which in turn sends a signal through the

pituitary gland to the adrenalin gland to produce the cortisol essential

to maintain fluid balance and blood pressure. Brain scans of the

amygdala (controls attention and responses) have disclosed excessive

activity when symptoms of PTSD are present.

The Pacific Standard published the results of a PTSD study that focused on the hippocampus, the part of the brain that is the storage house for memories. They found “Hippocampal shrinkage,” of all the terrible-sounding human ailments, is a common condition among post-traumatic stress disorder patients. It means a vital part of the brain is too small" and accounts for flashbacks. This study did not answer whether the smaller brain size is a manifestation of a predisposition for PTSD or a result of the stress. Other studies have been more definitive and linked the shrinkage of the brain to the incident of stress. Another study indicated that a smaller hippocampus would dull the response of a soldier that required immediate action, and to use the words of this particular study, "cause him to freak out". The article concludes "A traumatic experience can leave a defect in this molecular syste

We cited above Dr. J. Douglas Bremner in his definitive work on PTSD in the study entitled Invisible Epidemic relative to abused children. He also conducted studies with Vietnam Combat veterans with documented memory problems. He found a correlation of PTSD symptoms and a loss of neurons in the hippocampus. The brain image MRI) below shows, on the left, a normal scan, and the right side, PTSD. Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

Since 1980, the medical community had amassed a body of work that supported a diagnosis of post traumatic stress disorder. Newer studies have buttressed this approach. Physiological changes clearly connected PTSD symptoms to brain activity. The old theories that were staples in the military were about to be jettisoned. Public pressure was building for a new medical approach to this problem, and elected officials were getting the message, but it would take time for needed support from the federal government. Officially the soldiers symptoms were battle fatigue, and worse, tagged a cry baby or a coward. Fortunately, the bureaucracy began reacting to the immense pool of the mental health claims spilling out of the Vietnam War, and the public’s recognition that the problems of veterans were not being solved with home cooking. The Veterans Administration began to employ the services of more psychologists and psychiatrists]. The imprimatur of the federal government was now on board. PTSD was officially recognized as a wound and the government would support and fund studies and therapies with the Veterans Administration leading the way. Their activity is the "rest of the story". The VA now employs 21,000 mental health staffers and currently are actively recruiting 1500 more. In 2014, they will seek thousands more to handle the backlog.

Current treatment for post traumatic stress disorder must first address the guilt or shame so prevalent with those suffering from the illness. There are additional issues with use of therapeutic drugs as reported by the Veterans Administration:

Fear of possible medication side effects including sexual side effects

Feeling medication is a "crutch" and that taking it is a weakness

Fear of becoming addicted to medications

Taking the medication only occasionally when symptoms get severe

Not being sure how to take the medication

Keeping several pill bottles and not remembering when the last dosage was taken

Using "self medication" with alcohol or drugs with prescribed medications

Most recently, in a war time setting, Afghanistan and Iraq comes to mind, and rapid intervention and stress debriefing has been suggested as essential. Thereafter, group or individual therapy is recommended and it should be devoted to education on the subject of stress. Psychologists are strong advocates of cognitive behavioral therapy. In-take history must explore potential issues of early abuse, family history of drugs and, obviously, any repressed memories of combat--particularly searching for a significant incident that may have triggered the symptoms. That data is the template used to build a relationship of trust with the patient. The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs outlined the symptoms thusly:

Re-experiencing. Examples include nightmares, unwanted thoughts of the traumatic events, and flashbacks.

Avoidance. Examples include avoiding triggers for traumatic memories

including places, conversations, or other reminders. The avoidance may

generalize to other previously enjoyable activities.

Hyperarousal. Examples include sleep problems, concentration problems,

irritability, increased startle response, and hypervigilance.

The following anti depressant drugs are the most recommended to be used alone or in combination with other therapies: (Editor note on SSRI Drugs: A class of drugs that inhibit the uptake of serotonin by neurons of the central nervous system and are primarily used in the treatment of depression and obsessive compulsive disorder.)

Seratonin Reuptake Inhibitor (mood regulator)

Sertraline (Zoloft) 50 mg to 200 mg daily

Paroxetine (Paxil) 20 to 60 mg daily

Fluoxetine (Prozac) 20 mg to 60 mg daily Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

The torturous history of understanding stress took a dramatic right turn in Vietnam. Unfortunately, its current elevated recognition of cause and effect was dependent on the sacrifice of American soldiers. A cure for PTSD is still on the distant horizon, but evolution always seems to produce a winner.

Will any government ever award a purple heart medal for post traumatic stress disorder? Post Traumatic Stress Disorder

_______________________________________________________________

References and Sources:

Bentley, Steve. A short history of PTSD. VVA Veteran, Silver Spring, MD 2005.

Bremner, J.Douglas. Invisible Epidemic: Post-Traumatic stress Disorder, Memory and the Brain. Pandora's Project 2001-2009

Friedman, Matthew J. MD. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs

Gabriel, Richard A. No More Heroes. Prime 1987.

Klein, Sara. The Three Major Stress Hormones, Explained. Huffington Post, April 19, 2013.

Offley, Ed. Norman Schwarzkopf. Seattle Post Intelligencer October 6, 1992

The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Editor Ed Laurie J. Gale, Cengage 2011

The Gale Encyclopedia of Neurological Disorders. Second Edition. Editor Brigham Narins, Gale, Cengage Learning. 2012.

Return from Evolution of PTSD to History of American Wars Home