Mexican American Culture Differences

Cultural Clash in Texas

19th Century

Mexican Society North and South of the Border

Spanish adventurers dominated the age of exploration in the Americas in the 15th and 16th centuries. Their emphasis often was conquest and the imposition of their cultural and religious mores on native populations. However, their attempts to create settlements, put down roots, were hampered by their inability to populate them with European women. Inevitably, this led to intermarriage with native females. The genetic pool then produced a mixed racial ancestry in those areas that proved most potentially beneficial for Spanish exploitation.

Mexico, one such area, thus created a mestizo population infused with Spanish custom, language and religion. Inherent in this transfer of Spanish identity was the social order that made it possible to transfer this European culture to an accepting populace. The social order was basically feudal built on a three tier caste system.

At the top, were the large land operations (haciendas) that raised and exported cattle. Ultimately, this system would not prove commercially practical for Mexicans. Although Americans in Texas were ultimately successful in finding markets for their beef. The United States had a much greater non rural population for easier distribution of their product.

The hacendados, in Mexico, and in the early 1800's in Texas, held the political power. They were also well represented in the higher ranks of the Mexican military. Their vestiges can be seen in the beautiful Mexican architecture still extant in the modern southwest.

Descendants (hacendados) of the large landowners. |

|

The middle tier of Mexican society was composed of the small land owner (rancheros). Much like their American counterparts in Texas, they lived in one room adobe structures and completely dependent on their small patches for basic needs. Farming was less desirable than rounding up stray wild horses and cattle.

Abandoned Adobe in New Mexico |

|

.On the lowest rung was the peon. Much like an indentured servant, slightly above a slave, but not free. They required permission of the patron (estate owner) to travel and to marry. Their lot was servant to the upper class. Every aspect of their lives including fair treatment and justice were controlled by the owner. Punishment for minor or major offenses were defined by the law of the hacienda. During the many war years in Mexico and Texas, peons were pressed into military service in their local region. The peon's place in the military was the familiar bottom of the barrel.

Mexican American Culture differences

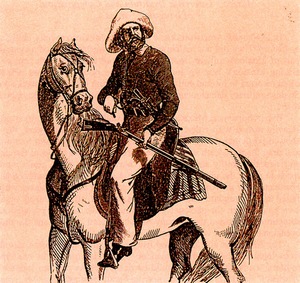

Although not directly in the caste system, the Mexican cowboy (vaquero) like the American cowboy and the Mexican clergy were integral parts of Mexican society.The clergy will be discussed in depth in an accompanying review..

The vaquero worked across class lines. His services were for hire and boundaries were no barrier. His contact with Americans in Texas was generally mutually respectful provided that cattle rustling was not an issue. The American cowboy tradition sprung from the Mexican vaquero that worked the cattle on horseback south and north of the Rio Grande border. The vaquero in Texas would drive cattle south toward Mexico City. That market, though, was tiny compared to the markets in the north serviced by the American cowboys.

In the passage of time, the Mexican cowboy was essential as the American west grew. It is estimated that they represented about 1/3rd of the cowboy population.

|

|

C.M. Russell

Mexican American Culture Differences

Then there was the Mexican military built on the Spanish model. It's highest officers were generally drawn from the wealthiest class and the ranks were filled with impressed peons and criminals released from Mexican prisons. In the southwest territories, they often acted as the civil administrators of regions, and acted independently of each other. In Texas, the central Mexican government had divided it into three separate regions. Mexican settlements tended to be established in the proximity of the military installations in Texas. In the territories of New Mexico and California, Mexican settlers tended to attach themselves to the Catholic missions which also offered employment to the lay population.

The American experience was wholly different. Their ranches tended to be isolated and quite independent of each other. Their Protestant backgrounds had no experience with religious mission life and their general contempt for Mexicans left little opening for peaceful interaction and religious tolerance.

Mexicans were traditionally respectful of authority

and accepting even when it was arbitrary. Americans were suspicious of and particularly disdained authoritarian rule. Their first

acts of armed defiance were often aimed at the local Mexican military. Destroying military effectiveness usually also acted to demolish the office of the civil administrator.The military commander and the administrator regularly wore the same hat. The military, like the priesthood and the vaqueros, were the only players that could navigate across the class lines and the rigid cultural differences.

Mexican American Cultural Differences

In 1821, Americans, either as existing settlers or those emigrating into Texas territory were confronted with an independent Mexico and a society outside their social experience. However, there were fissures in the rigid class system caused by ten years of war with Spain. As the Mexican economy crumbled, many of its institutions were strained. Mexico had been wealthy. Their precious metals had infused the Spanish crown with 75% of its revenues. By the time they won their independence, the mines were no longer productive and ranches met a similar fate. The banking system had collapsed. Barter became the coin of the realm in Texas.

The attempts by Spain, and subsequently independent Mexico, to populate Texas were a failure. They lacked the population to create large colonies. Those Mexicans that crossed the border did so with a strong sense of community. It was customary for entire families to migrate and immediately treat extended neighbors as family. These type of social relationships were beyond the experience of the American immigrants.

The wealthier Tejanos (Texans) often partnered with the local military. Their ranches formed the basis of towns that drew few American settlers who were deemed "loners". American settlers were independent actors and did not form extended attachments.

Initially the Americans were welcomed in Texas. They shared a mutual philosophy that favored local rule and less restrictions from the central government. However, the dichotomy existed in determining the local rule that best suited their lives. As the American population outgrew the Mexican settlers, the former sought American style administration that generally excluded the military interference that had always been part of Mexican life.

The caste system, so much a part of Mexican life, was badly frayed in the hard scrabble life of Texas that exposed them to Indian attack and the privations of a semi primitive land. Add to this, the Mexican belief that the American interlopers were crude and asocial while the Americans dismissed the Mexicans as ignorant.

There were exceptions. Some Americans understood wealth and power and readily accepted those at the top of the caste system. Stephen F. Austin, father of the Texas Republic, married the daughter of the Mexican regional governor. In the main, these attempts at racial rapprochement had little affect on Mexican American cultural differences.

The Mexicans had abolished slavery and the Americans, mostly southerners, favored bringing slaves into Texas. It did not pass the notice of anti slavery Mexicans that Americans were still bringing in African slaves and calling them indentured servants in order to avoid the Mexican anti-slavery laws. Americans applied their color prejudices to the brown mestizo settlers. This undercurrent of bias did not go unrecognized by the Mexicans, and served to exacerbate Mexican American cultural distinctions.

Those Tejanos not allied with the local military, and not recipients of the benefits that flowed from such an alliance, may have approved the American talk of independence. All the northern states of Mexico, along with their Tejanos brethren, disapproved of the central regulations that emanated from the Mexican capital. Some few were among the defenders in the Alamo along side of Americans. However, any potential, strong alliance was dashed when Americans used armed force indiscriminately against all Mexicans without distinction for individual political sentiment. If they were brown skinned, they were identified as enemies. Their property was forfeit and long held land titles did not prevent eviction.

The Texas Rangers were established by Austin to protect the American settlements against Indian attack. However, during the Texas war for independence they were involved in brutal attacks on Mexican civilians. Those attacks seem to have been counter intuitive. The minute population of Tejanos never represented a military threat, nor a threat to American independence. As late as the 1850 census, only 14,000 Mexicans were counted as part of the population of Texas.

Mexican American Culture Differences

Texas Ranger

Library of Congress

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Source:

Library of Congress

Texas State Historical Association

University of California

University of Texas Libraries

References:

Atlas of the American West, Beck, Warren A., Hasse, Ynez D., University of Oklahoma Press, Norman 1989.

The Encyclopedia of the American West, Simon & Schuster, New York 1996.

Tijerina, Andres, Texas A&M University Press

American Wars | Mexican American War | Mexican American Culture Differences