Revolutionary War Soldiers

Contents

British Ranks

American Militia

Continental Army

Hessian Soldiers

French Soldiers

Loyalist Soldiers

American Navy

Prisoners of War

Black Soldiers

Belligerents

Distinguishing Friend From Foe

Our collective image of Revolutionary War soldiers is the clash between the well trained, disciplined, veteran British “Redcoat”and the plain spoken, American citizen-soldier clothed in homespun.

This image persists despite some very worldly and sophisticated American leaders that filled the American officer corps. Not only is this picture somewhat out of focus, it fails to include the other relevant participants in this conflict.

In close combat, when microseconds determined life or death, the color and cut of a uniform provided the direction of a thrusting bayonet.

Variety ruled--the British in the iconic Red Coat, militia in homespun, the Continental Army with its personal choice of style and color. |

|

No retelling the story of Revolutionary War soldiers is complete without the insertion in the foreground the French and Germans clad in their distinctive uniforms. Harder to locate, in the background, is a hint of the Spanish and Dutch contributions, suppliers of war materiel as well as the cloth for some of the uniforms that found its way onto the battlefields.

French style-------------Hessian sense of order |

|

Elements Common

to the

Revolutionary War Soldiers

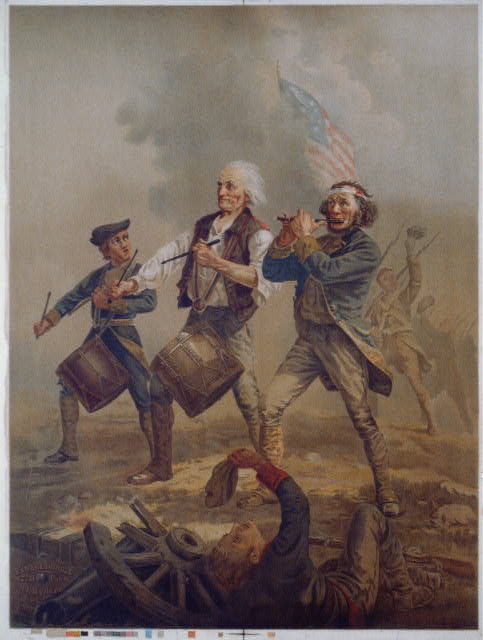

Soldiers of both armies had many common aspects in their lives.. The most universal was the beat of the drum. They awoke to the sound, marched to the sound, albeit to a different beat, and engaged in battle to the drummer's signal.

Food was often foraged from the local farms and contributed to the similar diets of the enemies. Early in the war, weapons bore the brand of English foundries and manufacturers. When Americans began to produce arms for their army, similarity was the rule.

|

The drum moved armies--(British Battles.com) (Library of Congress) |

Death of Revolutionary War Soldiers

Officers were expected to lead from the front. Their mortality rate was high. Both sides suffered losses. Officers of higher rank were often mounted increasing their visibility. Their colorful uniforms, some with gold braid, created targets of opportunities for sharpshooters. American General Montgomery falls at Quebec. (Library of congress0

American casualties were estimated at 25,000 dead and wounded. Over 2,000 would die over the winter in Valley Forge. British forces counted about 20,000 men in arms dead and wounded. The British ally, Germans (mainly Hessian) lost 6,354 men.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Filling the British Ranks

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Any study of the officer class in the 18th century is defined by the word “class”.

The ranks of British soldiers were a reflection of division and exclusivity as defined by social class. Not unlike the distinctions that existed in the English society of the day. There was an upper class and the commoner.The distinction was sharply enforced in their armed services. The officer ranks were based on birth and wealth and positions were for sale. Commissions were purchased at a price fixed by each regiment. Boys, as

young as 14, could purchase the lowest officer rank of ensign.

Vacancies created opportunities for advancement---

at a price. Merit advancement was non existent.

A further distinction was the position of the son in the family that followed the rules of primogeniture that devalued sons in the order of birth. The first son inherited the family title and all of its sinecures---the “landed aristocracy”.

Sons that followed the first in line of birth looked to the clergy for a professional life and finally to the army or navy for a career.

The navy was often a first choice for service. British policy favored their navy supporting it with large funding. The philosophy was that the navy protected the maritime life line of the island nation, produced its wealth, and secured its world wide commercial interests while an army was a financial burden.

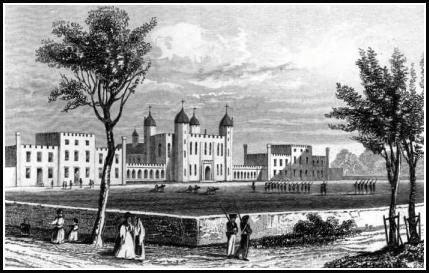

In the late 1700s, the world famous officers’ school, Sandhurst Military Academy, was still generations away. Thus training was on the job, and the learning curve depended on the length of experience and propensity to absorb military strategy. . There was an exception for the artillery man. Officers could be academically trained at the Royal Military Academy located at Woolwich, England.

Woolwich--Royal Military Academy

Graduating Revolutionary War Soldiers

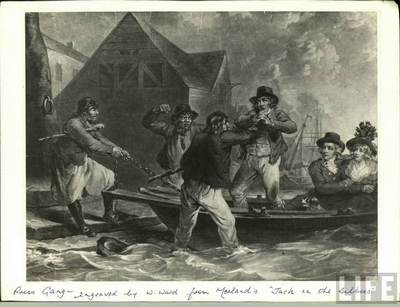

The non officer ranks maintained their social separation as well. The non-commissioned officer was a title earned on a merit and seniority basis. In the absence of an officer, his word was law, even in questions of life or death. Beneath him there were generally those men who were acutely poor and often “pressed” into service. Kidnapping by press gangs were sanctioned and paid by the regiment that employed them. Living conditions were harsh and their pay was less than one shilling per day from which was deducted costs for their equipment. These men had no particular dedication to patriotism or the King, and their loyalties were directed by training to the regiment in which they served.

Filling British Ranks with Revolutionary War Soldiers

British drill has been described as brutal, but served the purpose of enforcing strict discipline. Flogging was the common punishment for infractions. Some minor offenses were punished by hanging. The drill stressed a common reaction to battlefield conditions and suppressed individual action. Men were trained to form a line and square formation. Squares resisted cavalry charges, but lines were the heart of the battlefield. Two rows were formed. The first row would kneel and discharge their muskets at the enemy who were either charging them or in similar array across the battlefield. Immediately thereafter the second line would fire over the heads of their bent comrades providing a rotation for reloading time .

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Battle of Germantown

(National Archives-Engraving by Rawdon,Wright,Huch)

In 1775, the British Revolutionary War soldier was poor, probably pressed into service as an alternative to imprisonment (three regiments were composed of convicts), not respected by the English public, almost without exception not Catholic, and part of 11,500 stationed in North America. Those numbers would grow: By mid 1776, 27,000 men; by 1781, 56,000 Revolutionary War soldiers as part of a world wide British force of 110,000. Despite Irish enmity, Sir Henry Clinton was able to raise an all Irish regiment that participated in several campaigns integrating well with British units. The ethnicity of these troops did not raise any problems. Common in the lower ranks was the average pay of less than 1 shilling per day. Moreover, "enlistment" was for life but made allowance for families to travel with the soldier on foreign duty.

450 men made up the basic British regiment. The battle field array was 8 companies of musketeers lined up in the central front of the battlefield; on the left, a company of light infantry armed with rifles, and on the right a company of grenadiers----usually composed of infantrymen of imposing size and capable of throwing a grenade at long distances.

Within a generation, similar troops would serve the British public in a war against Napoleon. Those that filled the ranks were described by the Duke of Wellington as “the scum of the earth".

American Provincial Militia

Genesis

of Revolutionary War Soldiers

A nation in formation had no standing army. In early 1774, the number of men in a national army was zero in a population 2.5 million.

By the end of hostilities, 1783, 230,000 men had served in the Continental Army. Security was locally or provincially provided by militia manned by citizen farmers, merchants and tradesmen.

Many young recruits had no military training and little proficiency in the use of arms. Lower ranked officers were often the next door neighbor with the barest understanding of military discipline.

Some of the higher cadre had seen service in regular British or provincial units in the Indian wars (1756-1763). When their attention turned to resistance against perceived British aggression, they were lauded as patriots for the American causes of liberty and freedom. Owing to their ability to respond quickly, they were known as “Minutemen”. Patriots were also referred to as “sons of liberty”.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Militia

(Don Troiani)

The militia were the colonists’ only line of defense when Americans took the earliest English blows at Lexington and Concord. No militia units ever served in the Continental Army, sometimes along side of regular army, but under their local command. However, many militiamen enlisted in the Continental Army and joined the ranks of revolutionary war soldiers. These early enlistees were the most infused with pure patriotism which diminished, somewhat, in the ensuing years when a signing bonus was a required incentive for some.

In 1775, their sentiments about the English Parliament were echoed by a contemporary in “The Diary of the American Revolution”:

“A set of miscreants unworthy to administer the laws of the British Empire,have

been permitted impiously to sway. How unjustly, cruelly, and tyrannically they have invaded our rights".

Continental Congress Acts to Create an Army

Revolutionary War Soldiers

The Continental Congress met late in 1774. The Congress was essentially an association of ambassadors from the thirteen colonies. They held a common vision for the future, and the ability to read the handwriting on the wall. War with the mother country was on the horizon.

The Congress passed a resolution to build a national army. Their power to raise an army was dependent on the consent of the thirteen states. This lack of power was remedied in the future Constitution of the United States (adopted 1787 Article1. Section 8) which gave the Congress power to raise and support an army. Thus the congress was dependent on the legislatures of the individual states that had the right of conscription although recruitment was the norm in the militia system.

The several states were responsible for paying their soldiers and supporting and equipping the regiments they raised. A soldier's pay was consistent with their earning as a civilian, but some states added their own wrinkle. Many soldiers were promised cattle when their term of service ended. The term of service was considered a contract between the soldier and the Continental Army. Initially that term was for one year or the balance of the year of service in which they enlisted . It became a common practice to serve over the summer and leave in the winter. These men were known as “summer soldiers”. Terms of service, ultimately, would be increased to three years, and in the depth of the war (1777), the revolutionary war soldier would serve until the end of hostilities.

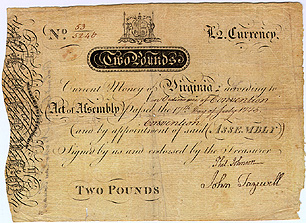

There is written evidence as early as 1758 that recruits were paid up to $400 (Virginia currency) for short term enlistment. Each colony, and later, each state, maintained their own system of currency

Currency of the Revolutionary War Soldiers

Virginia

|

Georgia (University of Notre Dame--Louis Jordan) |

. Table of Organization

The officer corps was created on a merit/experience basis rather than wealth. Commissions were not purchased. Many, like George Washington, had seen duty in the British or provincial armies in the Indian wars earlier in mid century. Washington may have had fond recollections of his militia service under British command, but that experience would be contrary to his beliefs as Commander in Chief when he sought to fill the ranks of his army. He decried the militia man’s lack of discipline, his carelessness with his weapons and cartridge boxes, and the short term of service that defied inculcating acceptable military training.

Order in the ranks was instituted when the Prussian officer Friedrich von Steuben offered his services to the Continental Army. General Washington granted him the rank of Inspector General. He then began systematically to install drill techniques that enhanced discipline.

The Steuben manual, "Regulations for the order and discipline of the Troops" was a top to bottom learning directive. He noted the significance of the non-commissioned officers. He detailed the responsibilities for each rank. His instruction for the sergeant major, the top non-commissioned officer in the ranks, taught them to recognize each soldier in the company, and to instruct the men beneath his rank in the necessity for absolute obedience. Additionally they were to keep minute records of each soldier, his former life, and pertinent data on his military career.

Von Steuben disseminated his training manual to all officers. It systematically, and in great detail, positioned troops in an array of battle lines positioned to repulse the enemy. His Article10 began:

"The changing the front of a platoon, division, or even a battalion, may be performed by a simple wheeling-----"

His teaching techniques included training a company of drill proficient officers. Upon competion of their training they were dispersed to join other regiments to act as trainers.

The Congress set the quota for regiments for each of the thirteen states that would make up the national army. . All complied. Massachusetts and Virginia each raised fifteen regiments with 800 men complements per each. Sparsely populated Delaware provided one regiment. Although Georgia and South Carolina filled their quotas, their regiments never served under continental command, but otherwise served with distinction. George Washington was appointed Commander in Chief on June 15, 1775. He would soon command 92 regiments. He was immediately dispatched to Boston to take command of 22,000 New England men at arms. Washington arrived in Boston two weeks subsequent to the Battle of Bunker Hill (June 17, 1775). General Washington was duly impressed with the men in his command, but must have had concern for the variety of battle dress which would persist for the entire war, and particularly when militias were involved.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Georgia Militia

(Don Troiani)

Washington brought with him very fixed attitudes learned from his earlier service in the Indian wars when the provincial militia served under British commanders. He believed that officers should me gentlemanly in manners and that discipline, not evident in the current colonial militia, absolutely essential in the Continental Army. Drill for the troops was the double line known as linear deployment. This required a front of troops kneeling and firing a simultaneous volley, and then the line standing behind the kneelers would execute an alternating volley. The lines were designed to rapidly change positions and configurations. In fact, Washington thought poorly of sniper fire from behind a wall or tree. He believed it would denigrate the American soldiers seeking support and recognition from European countries.

A novel idea executed in 1778-1781 bore fruit. A corps of light infantry was formed by choosing the best men from existing regiments and instilling the training that would be a model for all Continental divisions. Colonel Alexander Hamilton formed 10 such companies that performed extremely well at Yorktown (1781). Their reputation for high performance also marked the corps formed by General Anthony Wayne at Stony Point in 1779.

Revolutionary War Soldier

|

|

Alexander Hamilton

Although the provincial militias were not as significant in the prosecution of the war, the identification with the state of origin remained strong. It was customary to name regiments after the state of origin. Attempts to integrate soldiers from one state into a regiment of another state were futile. This insular state of mind was illustrated when a detachment of troops from New Jersey arrived at the George Washington winter headquarters at Valley Forge (1777). As was the norm, the men were required to sign a loyalty oath to the United States of America. Initially they refused. They claimed their country was New Jersey. General Washington attempted to resolve this type of loyalty problem when he ordered that all state names be removed from regimental designation, and, henceforth, each regiment was designated by number such as “20th Continental Regiment.

In contrast to the European armies, the Continental officer corps was quite egalitarian. Nevertheless, rank still had some privilege. Washington, in the opening year of war, had two housekeepers traveling with him to maintain his military household.

Washington maintained a ledger of personal expenses. His first purchase when he arrived at Cambridge after Bunker Hill was, as he expressed, " a ribbon to distinguish himself". Washington's expense records were maintained by Ebenezer Austin, and, then, Colonel Joseph Reed oversaw the proper execution of all payments. The National Archive maintains the meticulously detailed 66 page record which offers insight into the personal character of the Commander.

Hessians

Revolutionary War Soldiers

German troops represented about one-third of the British force in America. They were involved in almost every major campaign for the entire war. These men were regarded as the most highly trained and disciplined. Moreover, they were veterans of their successful Seven Years War (1756-63) prosecuted by Frederick the Great. It was his war machine that fought in America.

Those soldiers were initially feared by Americans and their Hessian General Wilhelm von Knyphausen gained a measure of fame. However their inability to execute efficiently over broken ground dimmed their reputation. Their forte was the open battle field.

They participated in many British northern campaigns, but ultimately many regiments were utilized as garrison troops. It should be noted that their 3 notable defeats at Trenton, Fort Mercer and Bennington were battles in which the British forces were almost exclusively represented by the German troops.

Frederick |

|

It is not quite accurate to designate all the German forces as Hessian. Although the bulk of the auxiliary forces came from the principality of Hesse-Kassel, a goodly number “loaned” were from six other German principalities. The “loan” of the soldiers cost the British about the current equivalent of 6 million U.S. dollars paid into the coffers of the seven German principalities. It is this system that differentiates the "mercenary" from the "auxiliary". The former understanding was based on a contractual system between a government and an individual. The latter rested upon a treaty between governments. This "auxiliary "method was reflected in the United States actions in Korea which integrated entire foreign units with the United States Army.

The "loan" of soldiers were the result of treaties with each sovereign German State. These agreements underscored the British inability to raise a home grown force in the face of public distaste for the English army, and , in contrast, the common opinion to support a strong English navy. Nevertheless, even its navy, would draw upon captured foreign seamen to supplement its ranks and a cause for further conflict between the United States and Great Britain in 1812.

The Germans, like their British cousins, named their regiments after their commanders. And like the British, the ranks were filled with the criminal, the poor and those pressed into service. Nevertheless, unlike the British, many of the German ranks were filled by a bounty system---not unlike American service. The Jaeger (hunter) rifle units attracted the best marksmen who received higher bounties and were considered the elite of the German forces.

The Prussian officer corps was highly prized and they populated many European armies. The British army in America was no exception. Nor were French and American Regiments exempt, but to a lesser extent. The rank of captain and above served an average of 28 years. Unlike other European armies, there was the possibility for non-commissioned personnel promotion into the officer class. As early as 1771, a military school was established in Hess-Kassel, Collegium Carolinium, devoted to academics as well doctrines of military tactics. The German soldier was somewhat a candidate of the merit system, and that may have prompted many thousand to remain in the United States at the end of hostilities..

Not surprisingly, Frederich von Steuben, Prussian born, brought his experience to the Continental Army and was awarded a commission of Major General. He was not the only German with sympathies for the American cause and the egalitarian society. At the end of hostilities, it is estimated that as many as 5,000 Germans defected and remained in the United States and integrated into its society.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

(Don Troiani)

Revolutionary War Soldier

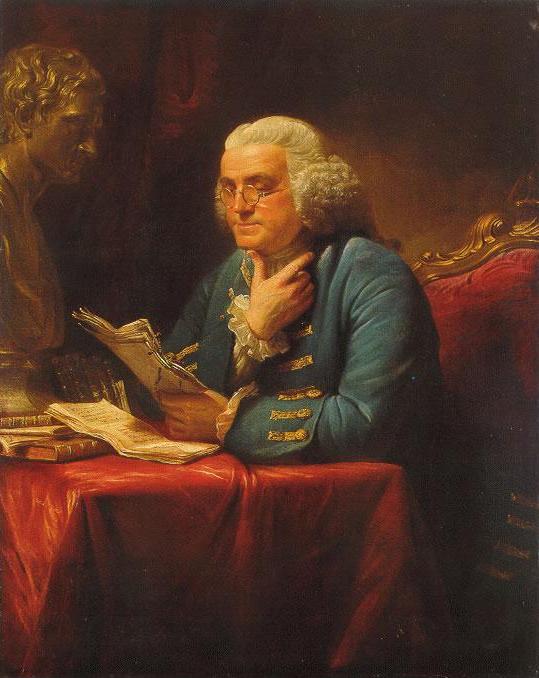

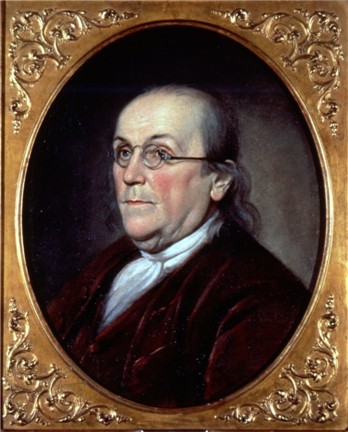

A thought must be devoted to a historical myth that painted the German forces as excessively brutal. One historian laid this myth at the feet of Benjamin Franklin who advanced this propaganda. The truth was that all, including the Americans, exhibited harsh tactics in the heat of battle. We are told that only the French soldiers had an ingrained respect for the property of others.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

French

Revolutionary War Soldiers

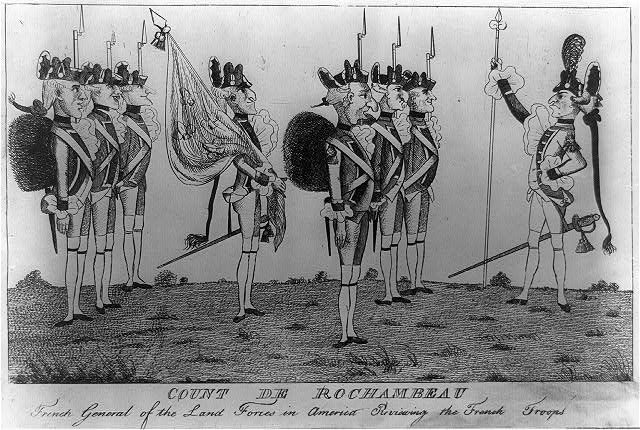

The French were the Americans’ lenders of last resort and fighting ally as the war progressed. Their war against the British, on sea and land, was prosecuted on two continents stretching and taxing British resources. They engaged the British on the Atlantic Ocean and two seas: the Mediterranean and the Caribbean. In the last years of the war, 1780-1781, eight Royal French regiments landed on United States soil, made camp in Rhode island, under the command of the Comte Rochambeau.

Their intervention, supplemented by their navy led by Admiral the Comte de Grasse, were instrumental in the British defeat at Yorktown. In their language, their action was the perfect execution of a coup de grace. French participation also included the technical support furnished by their professional military engineers.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Cartoon by contemporary Englishman

(Library of Congress)

As early as 1777, an adventurous, wealthy, young Frenchman, landed on the coast of South Carolina. The Marquis de Lafayette, armed with the recommendation of both Silas Dean, American agent, and Benjamin Franklin in Paris, sought to aid the American cause. He was granted a commission in the Continental army. His military credentials were unimpressive and relied on his captain’s rank of French dragoons ----trained to fight mounted or on foot. Some historians suggest that Lafayette's motivation to join with the Americans may have been for personal glory. The Continental Congress granted him the rank of Major General and he served with distinction in several battles.

February 6, 1778, France, by Treaty of Alliance, recognized the United States. One month later, Britain declared war on France. This was a redundant act that reflected a pre-existing state of war that would continue into the 19th century long after the closure of the American war.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

|

|

Franklin Dean Lafayette

Loyalists

Revolutionary War Soldiers

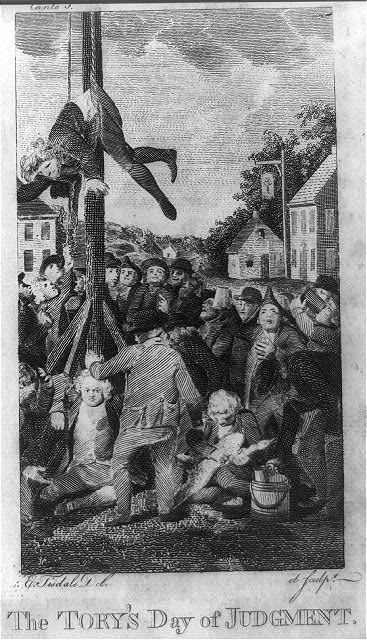

Financial pressures, partially created by British colonial rule, led to repressive taxation of the American colonies. Those in favor of this policy were known in Parliament as “Tories”.

In colonial America, this title was widely bestowed on those sympathetic with this tax policy---or dedicated to the English monarchy.

After the outbreak of war, acknowledged by the British as open rebellion in 1775, the appellation “Tory” was replaced by “Loyalist”.

The Church of England extended its conservative philosophy across the Atlantic and co-opted the pulpits of Anglicans making those congregations lean Loyalist.

However, that loyalty would not endear the Irish settlers to the Loyalist cause with their centuries old British enmity. The same was also true for German, Dutch and small Jewish populations. Although, these people had lived without any ethnic complaint under the English flag for a century. Once again, the English class system may have turned their sympathies to the American cause.

In the pre revolutionary war years, American’s were, in general, ethnically tied to the English. Their local governments were administered by British servants of the Crown whose allegiance bound them to uphold the laws of Parliament. Not only did the tax policy emanating from London divide the loyalties of the colonists between neighbors, but also formed cracks in the highest echelons of colonial government. This divided loyalty found expression when Thomas Hutchinson, Lieutenant Governor of Massachusetts, spoke in favor of Parliament’s right to tax, but insisted that taxation without representation was wrong. Across the Atlantic, the American public held mixed reactions to Parliamentary rule.

Thomas Hutchinson

Appearing in the Essex Gazette on March 16, 1775, this prescient comment by a Tory:

“This is the important crisis which will determine the fate of America.But hot men among you have extended your claims so far as to make it impossible for Parliament to comply, without relinquishing every shadow of authority”.

Divided loyalties within communities led to strange compromises. In New York, as reported in Holt’s Journal, March 21, 1775, the following excerpt:

“A few friends of liberty at Poughkeepsie flew a flag – on one side the King, on the other side , the Congress and Liberty”

This did not prevent Sons of Liberty from confiscating Loyalist property or enforcing ejectment or imprisonment. A jail for Tories still existing is exhibited below.. Execution was not beyond bounds. It is estimated that 20% of the country were Loyalists. Terror raids were a two way street. Loyalist, David Fanning, led guerrilla strikes in North Carolina. Their traditional conservancy or commercial interests with the British homeland bound them to the Crown. Many were rewarded after the war with parliamentary recompense for losses. There has since been sentiment that treatment of the loyalist was unjust. No greater evidence of division was the life long estrangement between Benjamin Franklin and his son, the Royal Governor of New Jersey.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Library of Congress |

Tory Jail

|

Post Lexington and Concord, April 1775, the harsh rhetoric rapidly descended to overt reprisal against the Loyalists. Many fled to New York City, a stronghold of loyalty to King George. Other loyalist friendly areas were located in Georgia and South Carolina. Loyalty oaths were sworn and signed to the King. Not every signatory intended to fulfill his obligation to the Crown; at least 20,000 ultimately filled British ranks either in the regular army or provincial units. Many acted as spies. Here is how one erstwhile Loyalist put it as reported in The Pausing American Loyalist:

“To starve on loyalty -Thus dread of want makes rebels of all”.

Some colonists loyal to the crown were active participants in the war. Many were integrated into the British army and led by British commanders and particularly engaged in the southern states. However, one Loyalist, John Butler, raised 10 companies of men and with Iroquois allies raided frontier areas on the New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania borders. Lt. Colonel Butler's Rangers focused on interrupting the food supply to the American army.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Butler's Ranger and Iroquois Ally

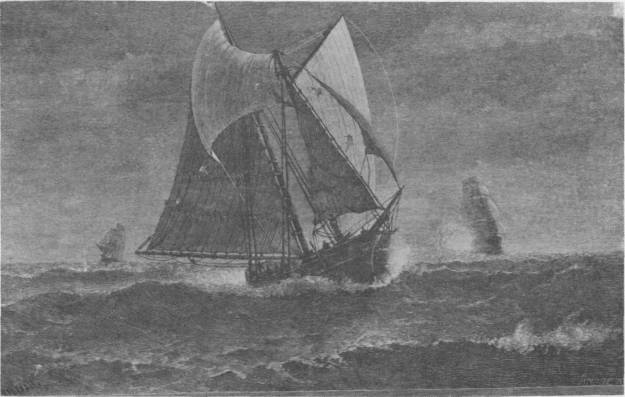

American Navy

Revolutionary War Soldiers

It would be malfeasance to omit reference to American sailors as revolutionary war soldiers. Their actions were a necessary adjunct to successfully fighting the British. As with a Continental Army, the Congress, in 1775, started with no ships. The first vessel to sail under an American banner was the “Hannah” launched September 5, 1775. Their object was to interdict and interrupt British supply routes to North America. Most states were coastal and protecting them from a superior British navy was essential. They faced a British navy with over 200 warships, but the American merchant fleet had a complement of skilled sailors that were the equal of the British.

Sailors Were Revolutionary War Soldiers

(MarbleHead Magazine)

Resources were in short supply and prevented the Continental Congress from building a large navy. As the war progressed, the Americans were able to rely on their abundant supply of timber and tar to increase their naval strength. What they were able to put to sea became a thorn in the side of the British. The Americans harried British shipping far from American shores venturing into English/European territorial waters.

One of the great stories of the war with the British was the escape of the trapped Americans on Brooklyn Heights (August 1776). Under the cover of darkness and dense fog, sailors from Marblehead, Massachusetts manned small craft filled with American soldiers and crossed over the dangerous currents of the East River to safety. They saved the army and its destiny. This naval feat was later repeated and depicted in the iconic painting of Washington crossing the Delaware (Dec 1776).

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Fraunces Tavern Museum

Prisoners of War

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Lest we forget the darkest side of war, captured soldiers may have sustained more privation, casualties and death than were caused on the battlefield. Each war seems to produce some blot on the moral fiber of an otherwise just society. When nothing appears to be amiss, it usually is the fault of historians or bad reportage. Historians appear to have gotten it correctly for the Revolutionary War. Most agree that all sides acted egregiously. Most of the brutal treatment of prisoners were with malice aforethought as a result of deep hatred, greed or both.

Americans captured by the British were not viewed as prisoners of war, but seen as traitors. Thus their lives were forfeit at any time while in custody. In some instances, officers were exchanged with American captors, paroled on the promise to refrain from further hostilities, and even under some sort of house arrest in the homes of loyalist sympathizers.

Colonel Ethan Allen formed the “green mountain boys” to protect the title to land he and other settlers owned and farmed in what was to become the state of Vermont. When hostilities with Britain began in 1775, he co-commanded with Benedict Arnold a force that captured Fort Ticonderoga. This was the first Crown owned property to fall in the Revolutionary War. He was later captured on the eve of an intended invasion of British Canada. He was deemed a traitor and imprisoned on a British ship and barely survived under the harshest conditions. When the prison population exploded, the British used unusable moored hulks. When he was later recognized as an officer he was imprisoned under better conditions in England, and later returned to Long island where he was paroled. He broke parole and was rearrested. In 1778, he was exchanged with the Americans for a British colonel. There is evidence that some who broke parole were executed.

Life for the common American prisoner never approximated the good fortune of Ethan Allen. He was either housed in England (as was the lot of captured American sailors) at Mill Prison, Devon or in some converted building to accommodate the captured Americans. The Devon structure still exists to this date.It is possible that some part of Allen's imprisoment was spent in the Pendennis Castle in Ireland.

A Prison for Revolutionary War Soldiers

The alternative could have been imprisonment in one of 26 prison ships; some off the coast of England or in New York Harbor. Life could be cut short for those with slight wounds as medical treatment was scant, if any. Sanitary conditions were abhorrent. Food rations were, when actually distributed, 2/3 of that for the common British soldier. There are reports that deaths in the prisons exceeded that on the battlefields and exceeded 10,000 Americans. Those reports also mention the improper diversion of intended resources by the less scrupulous jailers. Factually, Americans were deemed traitors and not deserving of humane treatment due a prisoner of war.

Revolutionary War Soldiers

Prison ship HMS Jersey

|

|

The Continental Congress with purer motives for prisoners held in their charge created a Commissary General for Prisoners to monitor prisons. They were charged with distribution of food, clothes and even money. The net result was, nevertheless, the death of thousands of British prisoners.

A word for a different kind of prisoner. The women and children of the patriots in service. Their families suffered economic privation and malnutrition. Properties were lost and many were rendered homeless. Some, who lost loved ones, would never recover after the war. Their lives also ended at Lexington and Concord.

American Slaves and Loyalists

Revolutionary War Soldiers

American recruitment problems and casualties in the ranks led to offers of freedom for slaves who joined the fighting forces. George Washington personally approved the offer. There was one such black man that previously joined the patriots in 1770 and died for the cause in Boston .His tombstone lies below. However, the offer, for the most part, was never acted upon, and the matter of trust may have eliminated any possibility of a successful “deal”.

On the other hand, it appears that black men were more sympathetic to the British Proclamation of Emancipation (1775) offered by Lord Dunmore (one time British governor of New England and then Virginia). He actually formed a force known as the Ethiopian Regiment which he led. As early as 1775, slaves escaped from their masters and reputedly 20,000 joined with the British in several battles, but most served in non combat activities. The actual number of black men serving in the British army is difficult to establish, but we do know that the Ethiopian Regiment had a complement of 800 black Virginia slaves, but were led by white officers and white, non commissioned men. Some blacks also participated in guerilla warfare.

Early Revolutionary War Soldiers

Crispus Attucks lies with other patriots, participants in Boston demonstrations.

Many Black escapees, believed to be as many as 100,000, fled to Sierra Leon in West Africa and some were participants in the disastrous engagement of the Great Bridge, Virginia. After the British defeat many of the Blacks embarked with Dunmore for Halifax, Canada.

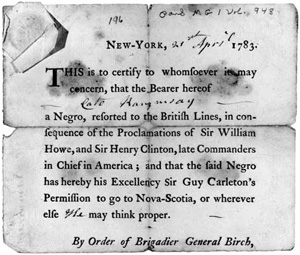

Black Revolutionary War Soldiers Escape

Safe Passage for African- Americans

Sources:.

Diary of the American Revolution. From Newspapers and

Original Documents, Frank Moore, C. Scribner, 1860 (Holt’s Journal)

Documents, Private Records Correspondence,Etc(Google Book).The Pausing American

Erwin, Art by. George Glazer Gallery, GGG.

Essex Journal. 1776-1777, Newbury-port (Mass.)The Diary of the Revolution: A Centennial Volume Embracing the Current Events in Our Country from 1775-1781 as Described byAmerican, British and Tory Contemporaries: Compiled from the Journals,

Ethan Allan Homestead Museum.

George Washington Escape. Fraunces Tavern Museum

George Washington, The Diaries of George Washington, ed. John C. Fitzpatrick(Boston-1925)

Jordan,Louis. Colonial Currency. Department of Special Collections, Notre Dame University.

Library of Congress.

Library of Virginia. Virginia Currency.

Loyalist, Middlesex Journal,

January 30, 1776.

Arms, L.R. NCO Journal Summer 95

Marble Head Magazine. "Hannah"

National Archives. Army Line Formation

Soldier of the King.The Valley Compatriot.Oct/Nov 1994, Donald Norman Moran ed.

Troiani, Don, Art by. Courtesy of www.historicalimagebank.com and National Park Service Museum Collection.

References:

A History of the British Army.13 vols. (London 1899-1930)

American Revolutionary War, A Student Encyclopedia,

Volume 1, Gregory Fremont-barnes, (ed), Santa

Barbara. Richard Alan, 2007.Berg,

Frederick Anderson. Encyclopedia of Continental

Army Units: Battalions, Regiments, and Independent Corps. Harrisburg, Pa:

Stackpole, 1972.

Curtis, Edward. The Organization of the British Army in

the American Revolution. New Haven, Ct; Yale University

Press, 1926.

Boatner, Mark Mayo. Encyclopedia of the American

Revolution: Library of Military History. Volume 1, Harold E. Selesky, (Ed),

Second Edition,Charles

Scribners & Sons, 2006.

Boatner, Mark Mayo.Encyclopedia of the American

Revolution. New York.

McKay, 1966.Brown, Wallace.

The Good Americans: The Loyalists in the

American Revolution. New York, William Morrow Company Inc., 1969.

Encyclopedia of Prisoners of War and Internment.

Second Edition. Jonathan Vance (ed). Millerton,

New York. Grey House Publishing,

Inc. 2006.

Frey, Sylvia. The British Soldier in America: A

Social History of Military Life in the Revolutionary Period. University of Texas

Press, 1981.

Johnson, Paul. A History of the American People. New York, New

York. Harper Collins Publishers Inc.1997.

McCullough, David. 1776. New York. Simon & Schuster. 2005.

Oxford

Companion to American Military History. New York New York.

Oxford University Press, Inc. New York. 1999.

Roberts, Kenneth. Oliver Wiswell. New York. Doubleday, Doran & Company,

Inc.1940.

Showalter, Dennis. Military History. Issue October 2007.